Jérôme Lejeune became the youngest professor of medicine in France when in 1964, at the age of 38, he assumed the country’s first professorship in fundamental genetics. His meteoric ascent was hastened by his discovery, in 1959, of the chromosomal basis for Down syndrome, ushering in the modern era of research into genetic disease, and abolishing the stigma of an illness that had previously been attributed to syphilis. Jérôme’s daughter, Clara Lejeune, paints a charming portrait of her father’s life in a biography called Life is a Blessing. She writes that his scientific genius was rooted in his habits “of contemplation and wonder,” and describes her father as a man of broad education and varied interests, whose “big blue eyes, a bit protruding, which sparkle with intelligence and humor, gaze at you with infinite tenderness. …Nevertheless they are demanding, too, because they love truth. They look, untiringly, for the why and how of what they see.”

Jérôme Lejeune became the youngest professor of medicine in France when in 1964, at the age of 38, he assumed the country’s first professorship in fundamental genetics. His meteoric ascent was hastened by his discovery, in 1959, of the chromosomal basis for Down syndrome, ushering in the modern era of research into genetic disease, and abolishing the stigma of an illness that had previously been attributed to syphilis. Jérôme’s daughter, Clara Lejeune, paints a charming portrait of her father’s life in a biography called Life is a Blessing. She writes that his scientific genius was rooted in his habits “of contemplation and wonder,” and describes her father as a man of broad education and varied interests, whose “big blue eyes, a bit protruding, which sparkle with intelligence and humor, gaze at you with infinite tenderness. …Nevertheless they are demanding, too, because they love truth. They look, untiringly, for the why and how of what they see.”

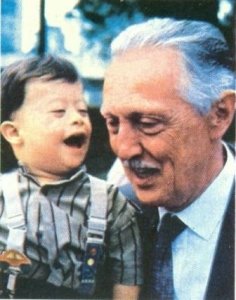

Clara relates that her father was above all a merciful man. Lejeune’s devotion to his family brought him home for three meals a day and evening prayer throughout his entire career. His love for his mentally and physically disabled patients inspired brilliant scientific research, but more importantly, it engendered an unwavering commitment to these “disinherited,” as he called them, “Disinherited because their genetic heritage was not perfect. Disinherited because they were the unloved members of this competitive, glamorous society.” When Lejeune became united with the disinherited, he found himself opposed to a society that valued perfection and convenience over the right of a person to live.

Lejeune’s scientific discoveries had, along with the newfound ability to perform amniocentesis, allowed physicians to diagnose Down syndrome in fetuses, which, combined with recent legislation on abortion, paved the way for millions of fetuses to be selected and killed on the basis of their disability. In 1972, Jérôme Lejeune stood in opposition to this atrocity when on the floor of the United Nations he publicly elaborated, for one of the first times in history, the genetic principles that confirm the completeness and uniqueness of each human life from the moment of its conception. Clara writes, “He knew, and he had proved it many a time, that in the first cell, from the very first day, the genetic patrimony is written in its entirety … Because every human being is unique, because he has an identity from the first day of his existence, because he is a member of our species, his life must be respected.”

In the years following his affirmation of “a scientific truth from which a duty followed,” as Clara calls it, Lejeune was “banned from society, dropped by his friends, humiliated, crucified by the press, [and] prevented from working for lack of funding.” He found solace, though, in a small league of sympathizers, and maintained his academic reputation and research support in the international community. He remained in his hostile homeland out of devotion to his patients, both born and unborn, and campaigned tirelessly for their protection under the law and throughout society. Lejeune established houses of hospitality for otherwise unsupported mothers, named Tom Thumb Houses after the unborn children that he loved so well. In 1974, Pope John Paul II appointed Professor Lejeune to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and in 1994 made him the first president of the Pontifical Academy of Life, a position Lejeune held for only thirty-three days before succumbing to lung cancer on Easter morning. At the very end of his life Jérôme wrote to a friend, “Just when it is imperative to defend the embryos…I’m out of breath. For the moment, faithful to the Roman legionary’s motto, ‘Et si fellitur de genu pugnat,’ I write, ‘And if he should fall, he fights on his knees.’” Lejeune was undaunted in his defense of the weak, even in the face of mortal suffering. He maintained a steady course throughout his entire life because he was oriented, like so many saints before him, by faith, particularly in the words of Christ in Matthew 25. Lejeune wrote, “One phrase, only one, will dictate our conduct, the expression of Jesus himself: ‘What you have done to the least of my own, you have done it to me.’” Lejeune forgot himself in service to the suffering and vulnerable because he realized that he was serving Christ, whose love strengthened him to become, as Pope John Paul II called him, “one of the ardent defenders of life,” and “a great Christian of the twentieth century.”

– Cliff Arnold

This article first appeared in the Spring 2009 edition of The Sign of Peace.